Welcome to Landmine Friday, Folks, when I go where angels (and all other intelligent Substack writers) are too smart to go.

Before diving into the meat of today’s newsletter, though, I wanted to briefly chat about two things. First, some of you have asked where the questions come from. The short answer is from you. Probably 90 percent come from the Ask Me Anythings I do monthly(ish) on Instagram. The others come from direct messages and emails you send me. I always get more questions than I can answer, so for the newsletter, I try to pick ones that require some time and thought, as well as questions I get frequently. The questions I most frequently choose not to answer tend to be about people or groups within the Church (I am not here to bash anyone by name), questions to which I don’t know the answer, and questions that are so specific to an individual that it would be better to put it to a friend or family member, not me, a stranger on the Internet.

Which brings us to the second thing I want to chat about.

The two questions I am answering today—about tattoos and altar girls— have come up multiple times in recent Ask Me Anythings. I have hesitated to answer them because while I don’t mind ruffling feathers on clear and pressing Church teaching, I am not so keen to do that on topics where the Church’s teaching is less clear, up for debate, or leaves room for more development. I hold a lot of opinions that I know are just that—opinions—and I prefer to be at least somewhat judicious in choosing the hills on which I’m willing to die.

Despite that, I decided to answer these two questions. This is partly because people keep asking specifically for my thoughts on them, not Church teaching, and thoughts I do have. I’m also answering them because I think it always serves us to examine everything more deeply, especially things many of us take for granted (like tattoos and altar girls). I hope, even if you disagree with me, that you know my thoughts here are offered in charity, more as musings or explanations of my own reasoning, than as Gospel truth or hard and fast judgements on anyone.

And with that, let’s get down to business.

What are your thoughts on tattoos? Do you think it’s okay to get one?

Before I share my thoughts, we should start with Church teaching, which on this subject is practically non-existent. The Church gives no official yay or nay to tattoos. She doesn’t say tattoos are good. She doesn’t say tattoos bad. She simply says nothing.

Now, the Book of Leviticus does include a prohibition against tattoos: “You shall not make any cuttings in your flesh on account of the dead or tattoo any marks upon you: I am the LORD,” (19:28). But the line before that also prohibits “round[ing] off the hair on your temples” and “mar[ring{ the edge of your beard,” (Leviticus 19:27). Both commands are considered part of the ceremonial law, which was given to the Israelites largely to prevent them from acting like their pagan neighbors and help them remain a people set apart. With the advent of the New Covenant, however, that law was no longer considered binding on Christians. This is attested to by both Scripture and Tradition. “For when there is a change in the priesthood, there is necessarily a change in the law,” we read in Hebrews7:12. Likewise, Saint Irenaeus of Lyon, writing around 180 A.D., explains:

“The laws of bondage, however, were one by one promulgated to the people by Moses, suited for their instruction or for their punishment … These things, therefore, which were given for bondage, and for a sign to them, He cancelled by the new covenant of liberty,” (Against Heresies IV.16.5).

All of which is to say, like with so many other aspects of life, whether or not we should get a tattoo is a question the Church leaves up to us. If someone gets one, it’s not a sin. It might not always be prudent. It might not always be wise. It might not always be a decision made soberly and with good intentions. But it’s not a violation of Church teaching.

I know some voices within the Church say otherwise. They do think it’s wrong and see tattoos as a kind of reversion to Old Testament paganism. And maybe, with some people, it is. But, on a much deeper level, I think the desire to get a tattoo is more often about our impatience than our godlessness.

Let me explain.

The Church teaches that the body is the sign of the person. It communicates the truth of who we are to the world, allowing us to know and be known, love and be loved, serve and be served. It does this in countless small ways every day of our life. Smiles communicate that we’re happy. Tears communicate that we’re sad. Our mouths and tongues allow us to tell people we’re angry. Our arms and hands allow us to show our children love. Even to just type words on a screen, we need our bodies. They make visible the invisible parts of us.

They also tell the story of us. Life writes a tale on our bodies. Laugh lines and callouses, stretch marks and scars, bright eyes and hunched shoulders all tell the world something about who we are. They tell the world we have spent our lives being kind, joyful, hardworking, and long suffering … or that we have spent them being vain, selfish, insecure, and fearful. Tattooed or not, our mortal bodies reveal something of our story to the world.

But that revelation isn’t perfect. In this world, the body can lie. We can smile when we’re sad. We can perform actions that don’t reflect our true intentions. There’s room for deception, as much as revelation. And even when there is revelation, it’s always incomplete. So much of who we are and who we will become can’t be seen. In this life, the glimpse of our soul that our body gives to others is always, at best, partial, bound by time and our own limited perception.

For those who love and follow Christ, however, this will change in the life to come. According to Catholic tradition, one of the properties of our resurrected and glorified bodies will be claritas or clarity. This means our bodies will fully communicate the truth about us, finally doing perfectly what they do now imperfectly. In Heaven, our bodies will reveal who we are, totally and completely, allowing all to see, at first glance, our unique beauty and all that has gone in to the making of that beauty. The people we loved, the crosses we bore, the stories that shaped us—all of that, somehow, will be evident in our resurrected bodies. Our story will be written into our very bones.

That’s the promise . That’s the hope. And it seems to me—and this is an Emily Chapman opinion, not a Church teaching—that most people who get tattoos are just fighting against the limitation of these earthly bodies. They don’t want to wait for the resurrection. They want to be fully known now. And they want their body to be what it’s supposed to be: a witness to the world of who they are and what they love and where they’ve been. They want claritas today, in this life. So, they tattoo names of lost loved ones on their back or symbols of places they’ve traveled on their wrists or literal tears on their faces, using their body as a kind of billboard to proclaim to the world their deepest loves, most formative experiences, and most profound suffering.

That desire is good. It is good to want to be known. It is good to want to communicate to others who we are. And it is good to want our body to be a part of that communicating. That desire comes from God. It reflects how He made us. It also points to where we’re going.

The problem, of course, is that tattoos can be as time bound as our bodies. Some people get tattoos they never regret, but others write names on their arm that eventually they’d like to erase. Or they tattoo grief on their face that remains there, even after it passes from their heart. They get a tattoo wanting their body to more perfectly express their soul, but often end up with a body that expresses their soul even less perfectly than before. Which isn’t good.

Again, none of this is to say people shouldn’t get tattoos. The Church doesn’t say this, so I’m certainly not going to say it. But I do think it’s helpful to try to name the longing behind so many tattoos. I think it’s good to know the thing for which people are truly hungering. And I think it’s good to know that we don’t need a tattoo to have that hunger filled. In His own time, God will fill it Himself, fully and completely. He will write our story on our bodies better than we can ever write it on ourselves. And He will do that in a way that will never age badly or elicit regret, but rather will perfectly reflect the glory, the beauty, and the wonder that is us.

What do you think of girls being altar servers?

Like with the question on tattoos, I’m first going to share the official Church policy, and then—because it’s what you asked for—I’ll offer my own thoughts.

The official policy of the Church today is that in the Latin Rite Liturgy women and girls can serve at the altar. For most of Church history this was not the case. Only men could serve. Then, as I understand it (canon lawyers correct me if I am wrong), the 1983 Code of Canon Law removed the male only requirement for acolytes. After that, some bishops in some dioceses began granting permission for girls to serve alongside boys. In 1994, Pope John Paul II formalized that permission, signing a Vatican document which allowed individual bishops, at their discretion, to permit women or girls to serve as acolytes on a temporary or exceptional basis. Finally, in 2021, Pope Francis issued a moto proprio which changed Canon 230, replacing the word “lay men” with “lay person,” and thereby allowing women to serve as lectors or altar servers on a regular (not temporary or exceptional) basis.

So, that is the Church’s current policy. It is not, however, a requirement: bishops can still choose to have only men and boy serve in their dioceses and priests can still choose to have only men and boys serve in their parishes.

It’s also not a doctrine. The Church’s policy about women serving is not a teaching about faith and morals. It is not a truth revealed by God. It’s just a rule pertaining to the liturgy that can be changed (and changed again) at the pope’s discretion.

Moreover, any pope’s decision to change that rule—either in one direction or another— is not held to be infallible. It might be a good decision. It might be a bad decision. The Holy Spirit does not protect the pope from making bad prudential decisions. That’s not a charism any pope has. Which means the faithful are not bound to agree with the pope’s decision on such things. You’re not a heretic for thinking girl altar servers are unwise any more than you are a heretic for thinking the Church never should have made Friday abstinence optional for Latin Rite Catholics. The pope sets the rules on things like this, but it’s okay to think he made a less than perfect rule. He might very well have.

Which brings us to the actual question, which was about my opinion. What do I think?

In most ways my opinion doesn’t matter. If you are a woman who has served as an altar server and that has strengthened your faith, I am grateful for that. If you have a daughter who is serving as an altar server right now and this is drawing her closer to God, than praise Jesus for that. I am truly glad for all the wonderful ways God works in the world to draw us to Him, and Him working through a woman or girl’s service at the altar is no exception.

But all that being said, no, I don’t think it is appropriate for girls to serve at the altar. And by appropriate, I mean “fitting.” I don’t think it is fitting for girls to serve at the altar.

Like with the tattoos, I will explain.

The most common objection to female servers is that serving at the altar is an early way to discern a priestly vocation. As the argument goes, many young men have heard the call to the priesthood through their time as an altar server, and allowing girls into the mix can deter boys from hearing that call, both by preventing boys from wanting to serve (because boys of a certain age often don’t want to do things perceived as “girly”) or (as they get older) by distracting them, pulling their attention away from what is happening in the Mass and towards the girl serving alongside them. Some people also worry about young girls deciding they want to become priests and becoming resentful of the Church’s prohibition against that.

Those concerns might be valid. But they’re not mine. Mine are rooted in the sacramental worldview.

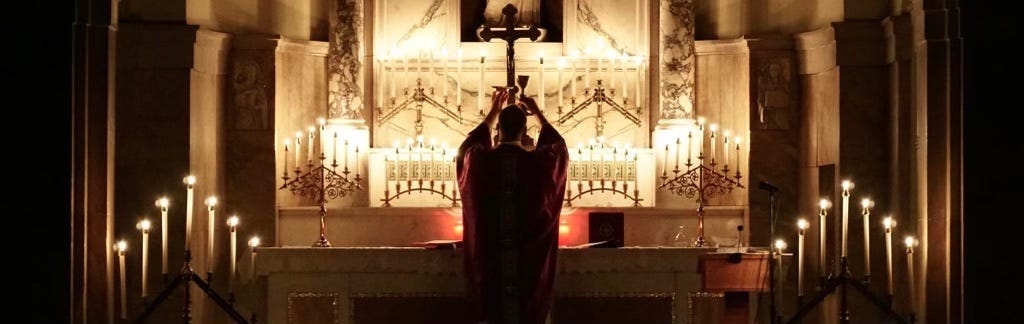

When it comes to valid celebrations of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, there are certain objective realities, things that are always true and always taking place whether or not the congregation sees it or feels it. For example, in the Mass, Heaven and Earth are truly united. In the Mass, the sacrifice of Christ on Calvary is truly re-presented. In the Mass, Christ truly feeds us with His Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity. And in the Mass, the faithful who are present truly give ourselves to God. We lay down our lives and for that moment, take our place in what C. S. Lewis called “The Great Dance,” God’s perfect plan for us, our lives, and the whole of the created world.

Our ability, however, to perceive those objective realities—to recognize and understand them and feel their weight—is dependent on symbol. The words and actions of the liturgy are symbols—or more accurately metaphors. They are things that point beyond themselves towards another thing, rendering it more knowable. The incense, candles, vestments, statues, bowing, kneeling, standing, the lifting of hands, the elevation of Host and Cup—it all exists so we can better grasp the objective reality of what is taking place. It’s all there, visible, so that we can start to perceive what is invisible: the Liturgy in which we are actually partaking, the Liturgy of the angels and the saints, presided over by the one, true High Priest.

What’s true of candles and incense, is also true of us. We are a part of this cosmic liturgy. We’re there as men and women, offering and receiving and laying down our lives on the altar. And we really are there as men and women. The Great Dance is not a gender-neutral dance. God loves sexual difference. He created it. He holds it in existence. And in the dance of the Liturgy, like in the dance of life, men and women have different steps to dance. We have different jobs.

If you were here for the great Manosphere Saga of 2024 (now unlocked for your reading pleasure), you might recall the tome I penned on authentic masculinity and femininity. Reflecting on John Paul II’s writings, I posited that the most essential task of masculinity is engagement. Men are called to be engaged—to give of themselves fully at home, at work, and in the world. They are made to be the living symbol of the Bridegroom, the servant of servants, the God who engaged so deeply with His creatures that He became one of us. Likewise, the essential task of femininity is to receive—to open our hearts and homes and lives to the other, to welcome love and truth and grace, to make room for the personal and the particular. In all that, we are made to be the living symbol of the Bride, the Beloved, the One who is transformed.

Because we are fallen creatures, however, living in a fallen world, being who God made us to be isn’t easy. Men struggle to engage in healthy ways, frequently falling into passivity or domination. Women likewise struggle to receive in healthy ways, just as frequently succumbing to passivity, pettiness, envy, grasping control, or manipulation. For most of us, engaging and receiving as we’re called to engage and receive is a tremendous struggle, often one of the foundational struggles of our life. We don’t know how to dance the steps we’ve been given. Which is why we need to practice them. We need to do them over and over again, until we become masters at them.

In Letters to an American Lady, C. S. Lewis describes what this learning process might look like for those who find themselves in purgatory, still not knowing how to engage and receive. For these people, Lewis imagines purgatory as a chaotic kitchen, where pots are boiling over and pans are burning in the oven and a million tasks need doing before dinner can get on the table. And it is the men who must do the work—who must take the pots out of the stove and the pans out of the oven, chop the vegetables, stir the sauces, baste the bird, and do whatever else needs doing. As for the women, Lewis says their job is to sit there and just let the men do it. The men must engage. The women must receive.

I love that image. I find it hilarious. But the goal, of course, is to never end up in that kitchen. The goal is to learn to dance the steps we’re supposed to be dancing now, in this life. The goal is for men to learn to engage and women to learn to receive before we die, not after.

The Liturgy helps us do this. The Liturgy not only reveals reality, but helps make reality more real. Sacraments are efficacious signs. They make possible the thing they signify. So, the waters of baptism really do cleanse us of Original Sin. The Eucharist really is food that imparts Christ’s Divine Life to us. The Mass does something similar. In the Mass, we worship God as He desires to be worshipped. And in the Mass, we become more capable of giving God the kind of worship He desires. Likewise, in the Mass, men and women image God as He made us to image Him. And in the Mass, men and women learn to image God as He made us to image Him. We take on the roles we’re made for—Bridegroom and Bride. We dance the steps we’re made to dance. And in doing so, we become more fully who we’re made to be. We learn the steps we’re made to dance.

Which brings us back to the question of altar servers. When we understand the liturgy through this sacramental prism, we can see that in the Mass, men, the symbol of the Bridegroom, fulfill their task of engagement by serving. They serve the Bride. They engage by getting out of bed and out of the pew and into the sanctuary. They lay down their lives as priests and deacons, as well as ushers and lectors and altar servers, with their service in the liturgy reflecting the service they’re called to give in their homes and in the world. They image for all of us what a God who serves looks like and what it means to serve like Him. And as they do that, they become more like that God. They learn to serve by serving.1

Likewise, women, the living symbol of the Bride, fulfill our task of receiving by not serving in the Mass, but rather by being served. We receive by not doing, not acting, not seeking to control or be at the center, but rather by sitting, contemplating, praying, and receiving all the grace God wants to give us. Our receptivity in the Mass reflects the receptivity we’re called to practice in the world—with hearts open to all God has to give and souls expansive enough for God and others to make a home within them. In the Liturgy, women show the world what it means to truly receive. We show the world the face of the Bride. We also show the world the face of Mary, who received God’s grace and magnified His greatness through that receptivity. And, like the men, as we do all that, we become more what we image. We learn to receive through receiving.

Again, this is hard. It is a task, one which many of us tend to rebel against, often because we’re confused: We think what is happening in the sanctuary is about power, not service. Or we think one role is more important than the other, that what women are called to do in the Liturgy and the world isn’t as vital as what men are called to do. A lot of the time, we don’t even know what we’re supposed to do. We’ve been told men and women have exactly the same steps to dance, that there is no difference, that we are interchangeable. All of that is how, at least in America, you end up with women doing everything at the parish short of offering the Mass, and men skipping Mass because it interferes with Sunday football.

So, yes, I do wish the Church still only allowed men to lector and serve as ushers and serve at the altar. Not because women aren’t perfectly capable of doing those jobs or less important than men in any way. But because symbols are powerful and when you mess with symbols you mess with people’s understanding of what is being symbolized. Men serving in the Liturgy and women receiving in the Liturgy proclaims fundamental truths to us and the world about masculinity and femininity, about the Bridegroom and the Bride, and about Christ and us. It also helps us live those truths more fully. Rules that tell men it’s their time to serve and women it’s our time to receive are helpful. We need them. They protect us from ourselves and our own fallen desires. They also encourage men to do what they need to do and women to do what we need to do, so that we all, together, men and women, can learn to serve and receive better.

The world is so profoundly confused on questions of sex and gender, men and women, fatherhood and motherhood, masculinity and femininity. It needs guidance. It needs clarity. And the Church has clarity to give. But it seems that we have allowed the world’s misunderstanding of the liturgy, the priesthood, and sex to trump our own understanding …. and compromised the liturgy’s witness to these truths accordingly.

But I am not the pope. These things aren’t up to me. And maybe I’m wrong. I very well could be. Maybe there is some greater good to allowing girls to serve that I can’t see. If there are, I am sure God will set me straight sooner or later. And if He doesn’t get to it, one of you will.

Five Fast Things

Another week, another podcast. This episode of Visitation Sessions is on “Chasing Childhood: Helicopter Parents, Free Range Kids, Gentle Parenting, and Us.”

My husband shared this quote on Facebook yesterday, and I think it’s worth sharing again here. It’s from Abuses in the Religious Life and the Path to Healing by Dom Dysmas De Lassus. It is a phenomenally important book which I have shared before and which should be required reading by every vocations director and novice master/mistress in the workd. Anyhow, the quote: “Too much asceticism, too much renunciation, not enough regard for the gradual way in which things progress or for the time that is needed, a lack of attentiveness to things that are necessary for the psychological life (such as healthy self-esteem, or the feeling of being useful), a mistrust of healthy initiative and legitimate autonomy, a lack of awareness of the essential need to be loved and recognized, or even a systematic discrediting of human qualities: long indeed is the list of those areas where a refusal to take the human conditions of life into account can have serious consequences, in the long term, for a person’s human and spiritual balance.”

I finally finished reading How to Stay Married: The Most Insane Love Story Ever Told by Harrison Scott Key. I have somewhat mixed thoughts on the last chapter, but if I had a friend whose marriage was struggling, this would be hands down the first book I would hand to them.

I shared this recipe for ridiculously healthy and ridiculously healthy Brownie Bites on Instagram this last week, but I am sharing it again here because it is really all I want to eat in the whole world right now. I made them for the kids, but now I am hiding them in the basement freezer, so no one can have them but me.

As I was getting ready to send this off, I got the news alert that Dame Maggie Smith passed away today, at age 89. I don’t think I have ever cried over the death of a celebrity, but I am crying now. What a treasure. What a loss. I’ll ask Chris if he is up for mourning that great lady by watching one of her wonderful movies tonight with a martini. Maybe Gosford Park? Or maybe we just need to start Downton Abbey all over again. Anyhow, many prayers for her soul and much thanks for her wonderful gift, which will go on blessing the world, even now that she’s gone. May something similar be said of all of us some day.

In Case You Missed It

“Food and the Feminine Genius” (Free for all)

“About ‘the Catholic Right’s Celebrity Convert Industrial Complex’” (Full Subscriber Only)

“Stupid Is As Stupid Does: On Politics, Prudence, and Priorities” (Free for All)

Obviously, every man in the congregation can’t be in the sanctuary. Most of the men will need to sit and receive what is being offered too. But the men who are called to serve on any given day are still witnessing to the truth of man’s call to engagement, and in that, helping men learn their call to.

This isn’t really a logical feeling but I went to Catholic schools for a few years growing up and the archdiocese (Boston) was absolutely wrecked by the sex abuse scandal. Most of the victims were altar boys and almost all served at a time when it was boys only. Girls are much more likely to report sex abuse (either witnessing or experiencing it). Never say never but I would be extremely hesitant to have my son serve as an altar boy where leadership insisted on boys only.

Emily -

I love your newsletters and I learn so much because you break it down for me. Thank you!!

I have 2 tattoos. 2 that remind me of my family and, particularly, of God. I have an issue with metals on my skin, so I chose to tattoo my consecration to Mary on my wrist rather than wear a chain. The other tattoo was before and is very symbolic of my life’s journey. I designed them both myself. I don’t regret them. I prayed long and hard about whether to have tattoos (even though I always wanted one when I was kid #rebellious). But I really agree that some tattoos are very rashly made decisions. Just stating a point I did not see in your newsletter. 🙂

As for altar serving - thank you for your opinions. I did serve as a girl when I was 12/13; it was something I could do since I wasn’t allowed to be in choir yet (my dad was the director). Learning more about the intent of altar serving, I definitely desire that only boys be allowed to serve. I have noticed more attention from the boys when only boys are serving and not with girls (of any age).

I know sharing your thoughts on these topics was a big leap. Thank you.